“Hello? I’ve got a bees’ nest in my bird box… can you help?”

So start about three phone calls per day here at Nascot Wood HQ at the moment (late May). Actually a fourth one usually starts “Hi… I’ve got a bees’ nest under my eaves / in my fence / outside my window”. A few brief questions later, we’ve usually established that the caller has Tree Bumble Bees (and probably have had for a little while).

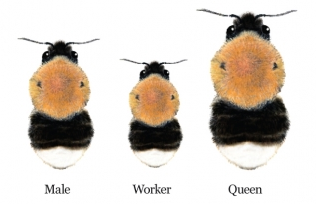

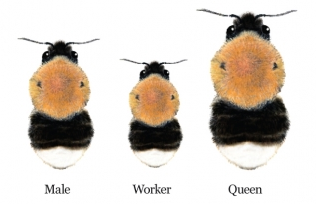

At this time of year, the tree bumble can make it’s presence felt due to a behaviour by the males, who are quite chunky insects. Up to a couple of dozen will fly around outside a nest, not going in, but orbiting about and making the air seem full of bees.

image by BumbleBeeConservation.Org

These are male bees – drones – waiting at the nest entrance for a new queen bee to emerge and go on a mating flight. It’s likely the nest has been there quite a while, but the small number of workers in the nest may come and go without being noticed. If you’re very lucky you may see a queen – much bigger than the others – emerge, and one of the lucky males mate with her, usually falling to the ground in the process. Once all the new queens have emerged, usually within a week or ten days, the drones will lose interest and disperse. Their “lecking” behaviour starts from soon after dawn until dusk.

Mating tree bumble bees (Nascot Wood Bees HQ, June 2015)

The good news is that a tree bumble bee nest will never get very big – not much bigger than fist-sized, and contain only hundreds of bees – not the tens of thousands of a honey bee colony. Any mating activity is likely to finish fairly quickly, and the whole colony will die out toward the end of July. In many cases wax-moth larvae will clean out the nest and, if located in a bird box (as many are), hopefully the intended occupants will use the site the next year. If the nest is in a roof space accessed through a small hole, you may wish to block the whole in mid-Autumn to prevent bees – and wasps – from using the space next year.

The bad news is that, of all the bumble bee species, tree bumbles are probably the most easily provoked. I deliberately avoid the word “aggressive”, because they’re not; but they will protect their nesting site and, in particular, they dislike vibration. So if they’re in a shed roof, for instance, they won’t like it if you slam the door, and may well sting. Unlike honey bees, their stings aren’t barbed so a single bee can sting repeatedly. They’re supposed to only deliver a small dose of venom, but having been stung by a tree bumble (when messing with their nest – my fault!) I can tell you it hurts!

So it’s best to avoid disturbing them, and certainly try to avoid walking through the lecking drones during mating time. If they’re located near a window, feel free to open the window but put up net curtains, sealed with tape around the edges, to stop the bees coming indoors – and shut (and open) the windows carefully.

As beekeepers, we’re happy to come out and re-home a swarm of honey bees. If we can’t keep them ourselves, (and we’ve only a finite amount of room / kit / time!) we pass them on to another bee keeper. Wasps we don’t touch. Tree bumble bees fall part-way between the two; in extreme cases, we may be persuaded to come and remove a bird box to a safer location. (As it happens, while I’m writing this the Beekeeper is out with some colleagues re-locating a tree bumble bee nest in a bird box; it’s in a public space and located at head-height right next to a footpath. It poses a risk to passers by but we don’t want to see the nest destroyed.) Unfortunately, as with honey bees, if the colony has taken residence in a roof space or high up, then we can’t help as we’re not builders and are not insured to work at height nor to dismantle your house!

So, there’s no need to call us if you have tree bumble bees, unless they’re really a significant public health risk. Please, enjoy these interesting insects, who are excellent pollinators, won’t damage your property nor pose a risk to other bees. If you’d like to make a contribution to a “citizen science” project, report your sighting to the Bees, Wasps and Ants Recording Society here.

Some further information about tree bumble bees – Bombus hypnorum

Tree bumbles are not native to the UK; they arrived here in small numbers in 2001 but have spread significantly since 2007. They now extend as far north as Aberdeen, and westwards to Wales and Cornwall.

They lack the common yellow or orange stripe of most bees; instead they have a ginger or reddish brown, noticeably furry, thorax (front part of body), a black abdomen, and always a white tip to their tail. Compared to many bumble bees, and certainly honey bees, they’re relatively round, rather than long.

Queen bumble bees go on “nest searching” flights in March and April, from which time the colony starts to build in size. Mating tends to take place in May / June, with the colonies reducing in size until few are seen after the end of July. The queens will leave the colony site and find somewhere else to hibernate over winter.

Queens very often choose bird nest boxes to setup home; they especially like it if there are already some “soft furnishings” such as down or moss, and have been known to evict bluetits from their nests. They will also find spaces under eaves, behind soffits, and in suitable holes in trees. Quite often you’ll see their nesting material partly blocking or bulging out of the entrance hole, below which may be yellow splodges – tree bumble poo.

For more information, see this article.